This post is intended to make an analysis of Cankam poems - it's major parts composed between 1st century BC and 3rd century CE - and try to interpret it through lens of available archaeological, epigraphic, material , numismatic evidences and more importantly along with contemporary western texts.

Cankam literature was studied in a period when there was very sparse archaeological data available. However, now the particular dark period of our interest has slowly begin to lit up. Therefore, it requires our immediate attention to analyse the archaeological data with texts. PJ Cherian of Pattanam excavations has already taken decision to Rediscover Tamilakam - he started it last year[2018]. His objective is same as us.

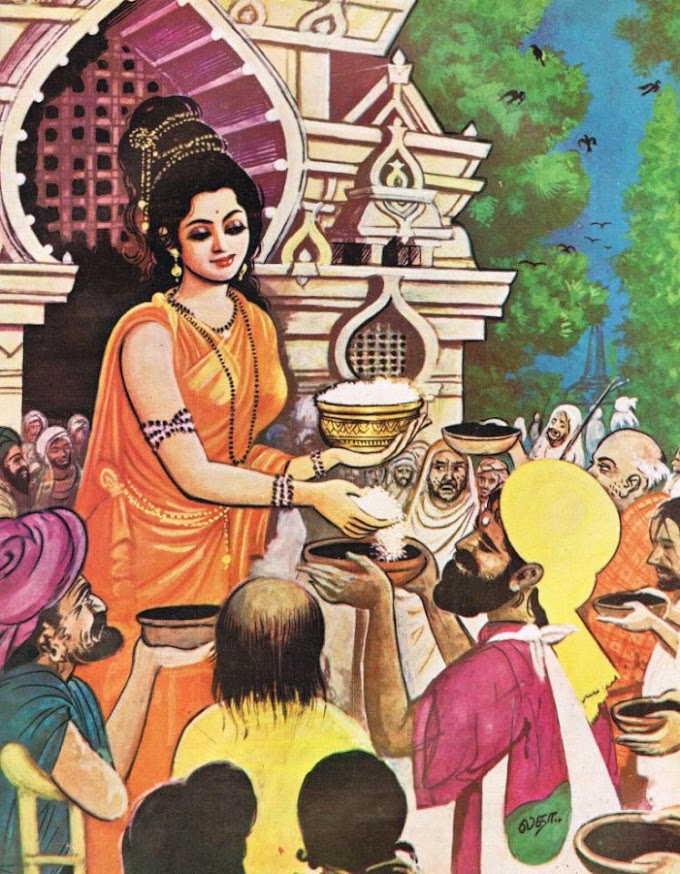

On reading through epics like Cilapathikaram and Manimegalai one may come to know that Tamilakam was a place of different merchants. Though these epics are dated much later, they reflect much of Sangam period.

The epic Manimekalai was composed by a grain merchant from Madurai called Cittalai cāttaṉār[சீத்தலைச் சாத்தனார்]. On the other hand the epic Cilapathikaram's hero's father was a merchant called mācāttuvāṉ [மாசாத்துவான்] and heroine's father was called as mānāykaṉ [மாநாய்கன்]. Though they are called as mācāttuvāṉ and mānāykaṉ , these are just titles to given merchants - not necessary their actual names.

Prof.John Guy says advanced Tamil goldsmith were operating as far as Southeast Asia. Guy says Tamils were dominant among the earliest Indic traders in East Asia (Guy 2011:248) .

Guy, John 2011 : 'Tamil Merchants and the Hindu-Buddhist diaspora in early Southeast Asia' in Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade : Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange.

Chaisuwan, Boonyarit 2011 : 'Early contacts between India and the Andaman coast in Thailand from the second century BCE to Eleventh century CE' in Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade : Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange.

Palanichamy MG, Mitra B , Debnath M, Agrawal S, Chaudhuri TK and Zhang YP 2014 : Tamil merchant in ancient Mesopotamia.

Cobb, Matthew 2018: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE-Brill (2018)

I.W Ardika 2018: ' Early Contacts Between Bali and India' in Shyam Saran's (ed) 'Cultural and Civilisational Links Between India and SouthEast Asia: Historical and Contemporary Dimensions'.

R. Muthucumarana , A.S. Gaur, W.M. Chandraratne , M. Manders , B. Ramlingeswara Rao , Ravi Bhushan , V.D. Khedekar and A.M.A. Dayananda 2014: An early historic assemblage offshore of Godawaya, Sri Lanka: Evidence for early regional seafaring in South Asia

Gunawardana, Dr. Nadeesha 2016: The Role of the Traders in Monetary Transactions in Ancient Sri Lanka

(6th B.C.E. to 5th C.E).

Ford, L. A. and Pollard, A. M. and Coningham, R. A. E. and Stern, B. (2005) 'A geochemical investigation of the origin of Rouletted and other related South Asian ne wares.', Antiquity., 79 (306). pp. 909-920.

Mukund, Kanakalatha 2015: Merchants of Tamilakam: Pioneers of International Trade

DiMucci, Arianna Michelle 2015 : AN ANCIENT IRON CARGO IN THE INDIAN OCEAN: THE GODAVAYA SHIPWRECK.

Appendix of Lankton and Gratuze in O.Benearapchi, Dissanayaka and Perrara 2013: 'Recent archaeological evidence on the maritime trade in the Indian Ocean: Shipwreck at Godavaya' in 'Ports of Ancient Indian Ocean'

Cankam literature was studied in a period when there was very sparse archaeological data available. However, now the particular dark period of our interest has slowly begin to lit up. Therefore, it requires our immediate attention to analyse the archaeological data with texts. PJ Cherian of Pattanam excavations has already taken decision to Rediscover Tamilakam - he started it last year[2018]. His objective is same as us.

I use Vaidehi Herbert's English translations on Sangam poems - available online at https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/. I use Tamil Lexicon [TL] of Madras university and Dravidian Etymological Dictionary [DED] by Burrow and Emeneau for meaning for some ancient Tamil/PDr. words.

Traders and Merchants guilds in Tamilakam:

On reading through epics like Cilapathikaram and Manimegalai one may come to know that Tamilakam was a place of different merchants. Though these epics are dated much later, they reflect much of Sangam period.

The epic Manimekalai was composed by a grain merchant from Madurai called Cittalai cāttaṉār[சீத்தலைச் சாத்தனார்]. On the other hand the epic Cilapathikaram's hero's father was a merchant called mācāttuvāṉ [மாசாத்துவான்] and heroine's father was called as mānāykaṉ [மாநாய்கன்]. Though they are called as mācāttuvāṉ and mānāykaṉ , these are just titles to given merchants - not necessary their actual names.

The names/titles like cāttaṉār,mācāttuvāṉ and mānāykaṉ are used as surnames by poets of Sangam poems. The former is used by many poets. While the latter two is used by 3 poets [ Perunkōḻi Nāyakaṉ Makal Nakkannaiyār , Āvaduturai Mācāttaṉār and Okkūr Mācāttaṉār ].

__________________

__________________

Analysis :

By removing the Old Tamil masculine case ending ṉ - however, the feminine term cāttaḷ does not exist - from cāttaṉ/cāttuvaṉ/cāttaṉār, we have now cāttu. The Old Tamil word cāttu(சாத்து) (<pkt. sārtha) means trading caravan (TL : 1362). Trading caravans were group of travelling merchants or in other words merchant guilds. Therefore, cāttaṉ/cāttuvāṉ/cāttaṉār are members of the group/guild of male sex.

The term mācāttaṉār or mā-cāttaṉār probably mean the head of the whole guild - the Pdr. word *mā means great,great man,superior etc.. (DED : 3923). Less occurance of the name when compared to cāttaṉ indicates that it is special title.

The meaning of the word mānāykaṉ , however, is not known definitely. However, Tamil scholars like Mayilai Seeni Venkatasami says the title most probably meant for merchants who involved in sea trade.

Epigraphic Perceptive :

The term mācāttaṉār or mā-cāttaṉār probably mean the head of the whole guild - the Pdr. word *mā means great,great man,superior etc.. (DED : 3923). Less occurance of the name when compared to cāttaṉ indicates that it is special title.

The meaning of the word mānāykaṉ , however, is not known definitely. However, Tamil scholars like Mayilai Seeni Venkatasami says the title most probably meant for merchants who involved in sea trade.

Epigraphic Perceptive :

The word cāttaṉ is attested in many Tamil- Brahmi inscriptions (Rajan 2011:181)(Mahadevan 1970:13 , 2003:481 ,1966:17,51,53,69). For instance, the Arachalur Tamil Brahmi has a name called tēvaṉ cāttaṉ(Zvelebil 1992:123). The name also attested in Sri Lanka (Pusparatnam 2002: 43,44,89) and also in Roman Egypt(McLaughlin 2010:36). It is probably the most popular Tamil name epigraphically.

______________

Discussion:

There are 21 poets with surname cāttaṉār in Cankam literature. While analysing the literary and epigraphic sources, the name/title cāttaṉ , it seems obviously, a popular name/title in Tamilakam and also in Sri Lanka. Association of cāttaṉār with traders/member of merchant guild is demonstrated above. However, it also noted that not all traders is expected to have had that name/title in Tamilakam.

There were merchants without the cāttaṉār title. Therefore, by going through epigraphic and literacy sources, there were merchant guild operating throughout the Tamilakam.

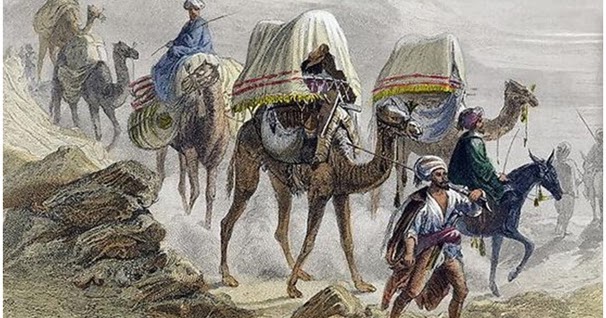

As they were merchant guilds they were not stationary - that is, they do move one place to another. Cankam poem Perumpānātruppadai (80-82) says Cāttus(s-plural) rode donkeys to travel. So, donkeys - or any other "cattle" for that matter- can be reconstructed as their mode of transport .

As they were merchant guilds they were not stationary - that is, they do move one place to another. Cankam poem Perumpānātruppadai (80-82) says Cāttus(s-plural) rode donkeys to travel. So, donkeys - or any other "cattle" for that matter- can be reconstructed as their mode of transport .

(Fig 1: Arab Merchants travelling in Sahara desert in Africa)

Prof. K Rajan brings a new term into play. Along with Cāttu , he sees another term called nikam[a] attested in Tamil Brahmi. The word nikamam carries same meaning as Cāttu (TL:2239). In Mangulam inscription there is a phrase called vellarai nikamattor (வெள்ளாரை நிகமத்துர்) - i.e. Trade guild from Vellarai (Rajan 2011:181). Rajan argues merchant guilds were developed before 3rd-2nd century BCE.

Merchants specialised in salt, sugar, oil, plough, gold, gemstones, cloth are mentioned in Tamil Brahmi inscriptions (Mahadevan 2003:141-42) suggests very much organised trade.

The Two inscriptions at Māṅguḷam of South India (nos. 3 & 6, ca. 2nd century B.C.E.) refer to the merchant guild “nikama” (˂Pkt. nigama) at veḷ-aṟai (Veḷḷaṟai), identified with the modern village of Veḷḷarippaṭṭi near Māṅguḷam (I.Mahadevan 2003: 141). A pottery inscription from Koḍumaṇal, knows as a place of manufacture of gems and steel, reads “nikā ma” (nikama) which indicate that merchant guilds were established at several industrial and trade centers in the ancient Tamil country. (Gunawardana 2016:113)

Merchants specialised in salt, sugar, oil, plough, gold, gemstones, cloth are mentioned in Tamil Brahmi inscriptions (Mahadevan 2003:141-42) suggests very much organised trade.

(Fig 2: A Kodumanal Graffito reading nikama. source: K Rajan.)

(Fig 4: Alagarmalai Tamil Brahmi inscription dated to 1st century BCE)

Prof.John Guy says advanced Tamil goldsmith were operating as far as Southeast Asia. Guy says Tamils were dominant among the earliest Indic traders in East Asia (Guy 2011:248) .

Cobb(2018:176-78) says that Roman goods would have most likely reached SE Asia through South India - as an intermediary.

Moreover, Tamil literary works also mentions about shipment of white horses (Perumpanaruppadai ) and usage of silks - both are peculiar to eastern trade. More importantly Pattinappalai(183-193) speaks about exports of SE Asian products into Puhar.

______________

The IRW is one of the fine ware and it is indigenous to south Asia. It most probably produced from 2nd c BC to 3rd c CE.

The ware's name is due to rouletting pattern in the ceramic and it is considered as inspiration from the Mediterranean ware.

It is generally considered as south Indian pottery. Nevertheless, Gogte(1997) suggested Bengal-Gangetic origin based on XRD analysis. The main problem of this theory is very few rouletted ware is found in Bengal region compared to South India.

Ford et al (2005) and Magee(2010) based on geochemical data argue they mostly produced in south India during 2nd c. BC.

S.K. Das et. al. (2017) argue, based on geochemical data , that the clay used to manufacture the vessel was from Kaveri region rather than Gangetic valley.

S.K. Das et. al. (2017) addresses the problem,

However, by analyzing geochemistry of clay, they conclude ,

Moreover, largest assemblage of IRW in a particular site is in western coast of India - that is, Pattanam from Kerala. Pattanam has 12,000+ IRW - more than any site in Indian ocean (Cherian 2015:749). Keezhadi excavations in two season from 2014-2016 has revealed 200+ sherd of IRW (Ramakrishna et. al. 2018:60). It is least likely that provenance of IRW could be outside the southern sub-continent and it also supported by it's distribution and recent geochemical data (S.K. Das et. al. 2017).

Shoebridge (2017), by analysing stylistic variances across the ceramics and manufacturing faults occurred during production of vessel concludes that IRW (and Arikamedu Type 10) production centers most likely around Arikamedu.

Diffusion of Indian Rouletted ware:

The Indian rouletted ware is found in many hundreds outside the subcontinent. We saw that IRW was more extensively used by South Indians - even if it was not originated there. In this context following should be understood.

IRW is found in Beikthano in Myanmar; Kobak Kendal (Buni Complex) and Cibutak in Java; Sembiran and Pacung in Bali; Tra Kieu, Go Cam in Vietnam; Palembang in Sumatra; Bukit Tengku Lembu in Malaysia; Qana in Yemen and Khor Rori in Oman and Myos Hormos, Berenike and Coptos in Egypt (Tripati 2017:6).

The rouletted wares found in Myos hormos, Qana, Khori Rori, Berenike and Coptos likely carried by Tamils from Muziris since the pottery is rarely found in west coast of India - Pattanam,however, is an exception here.

Chaisuwan (2011:94) says,

Other wares such as Fine ware 1, Fine ware 2, Fine ware 3, Fine ware 4 and Fine ware 5 from Arikamedu which show close resembles with wares found in Khao Sam Kaeo in Thailand is demonstrated through comparative studies(see Bouvet 2011).

Therefore, by tracing Rouletted ware - majorly distributed in S.India and likely originated in the same - one can see presence of south Indians across SE Asia.

Diffusion of Arikamedu Type 10 and 18:

In Bali, two sherds of Arikamedu Type 10 pottery is found along with Type 18,141, Rouletted ware and Indo-pacific beads. The Durham University has undertaken a project about Arikamedu Type 10 (see: http://community.dur.ac.uk/arch.projects/arikamedutype10/definition.html ).

I.W Ardika (2018) notes that,

Two hundred and twenty-two sherds of Arikamedu Type 10 pottery also found in Pattanam excavation (Cherian 2015:750). Presence of Rouletted ware and Arikamedu Type 10 in Egypt and Arabia is likely due to Tamils.

At the vicinity of Arikamedu, for instance, if the pottery makers were Tamils then who are they in the society? IAS R Balakrishnan brings two terms namely kuyavaṉ and kuyatti. There was a pottery making caste in early Dravidian society called as *kuyam (DED p.160). The men were called as *kuyavaṉ and women were called as *kuyatti. The female poet Venni Kuyattiyār - author of Puram 66 - belonged to kuyam caste

Glass Trade:

Apart from potteries, glass - in forms of beads and bangles - are best indication of Indian presence in SE Asia before common era.

There were two major glass making tradition in South and Southeast Asia - mineral soda aluminium glass and Potash glass. The mineral soda aluminium (henceforth m-Na-Al) is divided into five subcategories by Dussubieux (Dussubieux et. al. 2010)

One of the subgroup is m-Na-Al IU-hBa which most likely produced in Sri Lanka and S.India during 4th c. BC to 5th c. AD. The glass beads of Kodumanal (4th c. BC) , Alagankulam (3rd c. BC), Giribawa(3rd c. BC), Ridiyagama (4th c. BC) and Kelaniya(3rd c. BC) are analysed and they do share same glass type - m-Na-Al 1 or m-Na-Al IU-hBa. This type of glass diffused into Early historic SE Asia.

Very early glass in Southeast Asia had m-Na-Al 3. However, in later period m-Na-Al 1 type dominates. This may indication of extensive contact between southern subcontinent and SE Asia from 300 BC on wards.

The Godawaya shipwreck found in Sri Lanka dated to 2nd c BC contained glass ingots (Muthucumarana et. al. 2014).

According to authors and O.Bopearchchi , the vessel was made in southern subcontinent and is voyaged from TN to Lanka - or other way around.

Therefore, it confirms the glass trade between Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu. It also explain why the glass found in Lanka and Tamil region are same.

The shipwreck also proves existence of maritime route between Tamilakam and Lanka prior to Roman contact and existence of advanced maritime technology.

The Karava(<Ta.Karaiyar) were ancient Tamil tribes and they lived in Lanka. The Sinhala Brahmi inscription read as Dameda Karava navika. The Sanskrit word navika mean navigator of the vessel.

The karaiyars [< Pdr. *karai : coast (DED p.120) ] were most likely seafarers and they did captained the vessels!

Dussubieux and Gratuze(2013) notes that potash and m-Na-Ca-Al glass found in South Asia is in very few colours compared to Southeast Asia. The Dark blue color is represents of major of Potash glass in Arikamedu.

It looks plausible from the data that absence of dark blue color in locally manufactured glass forced the Tamil traders to trade for Potash and Arika/m-Na-Ca-Al glasses from SE Asia or China through Arikamedu.

Based on Glass data, Dussubieux et. al. propose three trade spheres existed during early historic period between South and Southeast Asia.

Presence of Mediterranean glass - and other Mediterranean artifacts - suggests direct contact with Arikamedu, an Indo-Roman trading station in Coromandel coast. Therefore, we have all reason to suggest a direct trade between Thai coast and Coromandel coast. Periplus (v.60) also confirms it.

The glass data emphasize trade network that existed between South India and Southeast Asia from early historic period. The data also supported by pottery evidence (demonstrated above) and epigraphic evidence in form of Tamil Brahmi inscription.

By analysing pottery evidence along with glass data, epigraphic data, Arikamedu 's connection with Mediterranean, statement from Periplus (60) and verse from Pattinappalai (183-93), it is very obvious that Coromandel coast was in a nodal position in world economy. As Cobb(2018:176-78) suggested, it is very much likely that Arikamedu was the source for Roman artifacts in SE Asia.

Kannan on describing rich street of Poompuhar says,

Kannan - author of the text - notes many minutes things that happen around the Puhar and recorded it perfectly. Though the kāḻagam mentioned in original text - in Tamil - is identified with modern state of Burma, I think it is reference to Malay/Thai peninsula. He did not mentioned what product was imported from SE Asia, nonetheless.

The original text in tamil has an important phrase 'குணகடல் துகிரும் '(kunakadal tukirum) , though missed in herber's translation. The Old Tamil word kunakadal literally means 'eastern sea' - i.e. Bay of Bengal. The Old Tamil word tukir means red coral (DED p.287).

Kannan records shipment of horses from overseas. He,however, was not aware from where it is shipped. He also records shipment of horses in his another text called as Perumpānātruppadai (319-20).

______________

Presence of Tamils/Malayalees in Western ports during early historic period is fairly established beyond doubt through archaeological ( materials like Indian cloth, coconut, teak, coir, and pottery ) , epigraphic - Tamil Brahmi inscribed names - and genetical evidence.

Apart from major ports, however, Tamils travelled inland.

Palanichamy et al. 2014 - a peer reviewed genetic paper published in PLoS One - concludes that two samples taken from Mesopotamia region belonging to late Roman period had closely matched with individuals from Dindigul region - a district part of Kongu region of Tamil Nadu. The apparent absence of the particular mtDNA in surrounding region and their presence in modern Dindigul district is the evident.

Therefore, cāttuḳḳal played a great role in connecting West with East and vice versa . During early historic period specialisation in gems, iron and steel, glass bead, pearl fisheries, cotton textiles and agricultural expansion helped the trade sustained for centuries - excavations in Pattanam, Arikamedu and Alagankulam revealed their heyday lasted for more than half a millennium.

As Peter Magee(2010:1052) suggests,

due to extensive contact with wider world, there was immediate reaction in the society. The Merchant guilds rose and they did called them as cāttaṉ . Specialisation in craft did arise and they also did work at other part of the world . As seen from glass data of Arikamedu, to satisfy/sustain the trade unavailable products were traded from one world and exported to another world.

Kings - or Ta. venter- showed immense interest in the trade. As Magee states, large reservoirs and ponds were built in Tamilakam around 2nd-1st c. BCE.

De Romanis says, Pliny the Elder estimated Rome’s annual deficit caused by imbalanced trade with India at 50m sesterces (500,000 gold coins of a little less than eight grammes), with “Muziris representing the lion’s share of it”

Due to Indo-Roman and Indo-East trade immense wealth flowed into Tamilakam especially in capital cities and port cities. It is much reflected in Pattupattu.

A Madurai Kanchi verse describes markets in Madurai as such,

In Puhar,

Therefore, early historic period is period transition from an agrarian based economy to Industrial economy and I emphasize that during this period there was - without any doubt - organised merchant guilds were operating in Tamilagam. They did trade, from glass to pepper, with area from Coptos to Bali.

Apart from cattan and macattan, there rose kiḻavaṉ / kiḻatti - land owner/ Chief of an agricultural tract , kiḻār & uḻavaṉ - agriculturists, ūraṉ - Chief of an agricultural tract / head of village, kāviti - title awarded for best agriculturist ,kaḷamar - Inhabitants of an agricultural tract , makiḻnaṉ - head of agriculturist tracts , patan - goldsmith, vaṇikar - general trader, kuyavan - pottery maker, kaṇṇavar - ministers, tāṉai - army etc..

K Rajan comments,

For instance, in Marutam lands,

kiḻavaṉ , kiḻatti , ūraṉ and makiḻnaṉ are land owning people and superior. On the other hand kaḷamar and uḻavaṉ are workers/subordinates. On the lowest, there was aṭimai (Puram 399), paṟaiyan, tuṭiyaṉ, pāṇaṉ, and pulaiyan and they did work in agriculture tracts, palace , as bards, servants etc..

Among traders, there was vaṇikar (<Pkt. vanija) - general trader , cattan (<Pkt./Pali sarvaha)- member of the guild and macattuvan - head of the guild. Among the rulers, the venters were superior followed by velirs, mannan, kurunila mannan etc..(Rajan 2014:33-6)

_____________

The reference to tolls appear in Cankam texts like Pattinappalai , and Perumpanaruppadai and post Cankam text of Kural (~450 CE).

Ancient Tamils used word ulku (<Pkt. sulka)(TL:) to denote toll. The Dravidian word *vari was used to denote tax, though both words more or less mean same.

The tolls were collected and they acted as revenues to kingdom. Since Tamilakam was a place where international commerce took place, immense wealth accumulated and therefore kings collected tolls from merchants.

Analysis:

Pattinappalai verse (116-25) states,

English translation:

they[collectors] do collect tolls continuously without any rest ,fail or break throughout the day!

Therefore, Tamil Kings collected tolls/tax regularly in major ports/cities to increase their revenue. From the verse, the tolls were collected throughout the day! Immense wealth could have accumulated due to tolls to the Chola state.

Ancient Tamil economic treatise Thirukkural 756 states,

Though Kural composed around 450 CE, it says why ulku mentioned in Cankam texts were collected. Moreover, Kural is not separated by vast time period from Cankam period.

Cankam poem Perumpanaruppadai states:

The Tamil word peruvaḻi generally means highroad. The medieval highway called rajakesari peruvaḻi was built by Chola king Adithan and it runs through Coimbatore region.

Epigraphically the word in it's Prakrit form is attested in Lanka.

The suka/sulka was collected in ancient Lankan port of Godapavatha by the monks. The Pattinappalai also projects similar scenario. However, in Puhar and Kanchipuram , tolls were collected by the officials of the Chola kingdom rather than monks/priests.

Therefore, we can hypothesis that Venters collected tolls from the merchants, though we are not in position to say if coins were used to pay the tolls. It is impossible to think that coins were not used to pay tolls. If we barter was used ,then it raises questions like what was bartered to pass the tolls and how it benefited the state - or the chiefdom?

The palghat pass played a great role in connecting Muziris and Karur. Many Roman, Greek, Chinese, Satavahana and local coins were found in and around these regions. Since palghat pass is a major trade route there must be tolls collecting stations and those coins could have used for payment of tolls. If local coins were not used for transaction then it raises the question about their purpose of existence in thousands of numbers. All three Venters, along with some chieftains/chiefdoms, issued coins. (see R. Nagaswamy's Roman Karur for local coins in Karur)

Customs officials :

In Cholan city of Puhar, the tolls were collected by officials from Cholan administration rather than priests/monks. The Pattinappalai(126-36) speaks of Cholan custom officer punching Cholan symbol on the products imported.

Nachikinyar commentary says they were officials from Cholan administrative. From the verse, the officials were given job of punching/stamping the Cholan symbol on the product to mark the authority of the state. This suggests a systematic organisation.

The following Silapathikaram verse about Puhar also confirms it.

____________________

As Mukund(2015:34-5) says, one of the major role of state is to protect the traders and trade routes from highway robbers. Whenever there is danger to trade route the state has to respond.

The obscured verse from Puram 126 (14-6) says,

From the verse, the angry Cheran army (ciṉa miku tāṉai vāṉavaṉ : tāṉai = Army (TL:1862) ; vāṉavaṉ=Cheran title.) did not wanted other vessels to sail in the western ocean (aṿṿaḻi piṟakalam celkalātu : kalam = small vessels) when they bring gold through their vessels (pōlantaru nāvāy ōtiya: nāvāy = huge vessel)

Why Cheran army did not wanted other boats to sail in ocean when they bring gold ?

The answer to the question can be obtained through Pliny's statement in his Natural History. Pliny says the Musiri was subjected to attacks from the pirates of Nitrias.

Pliny says, "[Muziris] was not desirable place for call, pirates in the neighbourhood". Pliny says, due to pirates, Muziris was losing it's importance to Nelcynda - a Pandyan port in Kerala and Nelcynda offered good cargo unloading service than the Muziris.

(Fig 13: Muziris in the 5th century CE Tabula Peutingeriana )

Now the Puram (126) makes good sense to us when we study it along with contemporary text. Pirates in the ocean must be causing great danger to Cheran economy and their port of Muziris. Though the verse did not mention Muziris nor Yavanas, the gold mentioned in the text must be Roman import. Romans used their gold coins as bullion. Due to piracy, the Cheran subjects did not allow other vessels to sail in the western ocean. Moreover, there are numerous reference to naval strength of Chera kings in the Sangam literature. I cannot reproduce everything here. It's beyond the scope of the subject. The occurrence of the word katalpadai (கடற்படை) - i.e. Navy - in Puram (v.6 :12) suggests existence of a navy. Existence of navy is not unlikely.

The Cheran motivation to control the piracy in the trade route through his organised army suggest a good level of political organisation under them.

Arikamedu in particular shows well-attested trade connections with Southeast Asia, and may even have been responsible for the diffusion of beadworking techniques in the region.It is far more likely that Roman goods reached Southeast Asia via intermediaries, just as Eastern commercial products could be acquired in Indian ports, like turtle shell from Chryse at Muziris and Bakare.The author of the Periplus explicitly refers to boats from the southeastern Indian ports of Kamara, Poduke (Arikamedu), and Sōpatma sailing not only to Limyrikē (on the Malabar coast) but also to the Ganges region, and across to Chryse (vaguely eastern or south-eastern Asia)

Moreover, Tamil literary works also mentions about shipment of white horses (Perumpanaruppadai ) and usage of silks - both are peculiar to eastern trade. More importantly Pattinappalai(183-193) speaks about exports of SE Asian products into Puhar.

______________

Indian Rouletted ware (IRW) :

The ware's name is due to rouletting pattern in the ceramic and it is considered as inspiration from the Mediterranean ware.

It is generally considered as south Indian pottery. Nevertheless, Gogte(1997) suggested Bengal-Gangetic origin based on XRD analysis. The main problem of this theory is very few rouletted ware is found in Bengal region compared to South India.

It is generally agreed that rouletted ware was locally made in only a few centers, probably in Tamil Nadu...We find it difficult to accept Gogte's argument that it all came from Bengal where very little, and that not typical rouletted ware, has been found. (Bellina and Glover 2004:78)

Ford et al (2005) and Magee(2010) based on geochemical data argue they mostly produced in south India during 2nd c. BC.

The question of where IRW was produced has also been debated. Coningham et al. and Begley suggest an origin in the southern areas of India and Sri Lanka (Begley 1988: 439). Schenk, relying upon limited XRD analysis conducted by Gogte (1997) and fabric similarities with Northern Black Polished Ware, raises the possibility of a northern, Gangetic origin for this ware (Schenk 2006: 136). This supports Schenk’s argument that IRW is connected with Mauryan diplomacy and, possibly, the spread of Buddhism. Since XRD examines the mineralogy of ceramics, not their geochemistry, it is not the most sensitive index of production origin over the vast distances of the Indian peninsula. Indeed, there is no reason – or evidence – to support the assertion that there is only one production source for IRW throughout south Asia. Coningham et al.’s suggestion that the IRW found in southern Indian and Sri Lanka is probably produced somewhere in that vicinity is not contradicted by any archaeological evidence. (Magee 2010:1044)

However, these studies need further investigation because XRD is not likely to be conclusive in assigning geological source, and the NAA result is based on only 10 samples. Nor did these studies include Grey ware and are hence lacking a temporal perspective (Ford et.al. 2005:911)

S.K. Das et. al. (2017) argue, based on geochemical data , that the clay used to manufacture the vessel was from Kaveri region rather than Gangetic valley.

S.K. Das et. al. (2017) addresses the problem,

Recent researches have emphasised that the fine wares of southern India and Sri Lanka are produced at a ‘single longrunning major production centre’ (Ford et al. 2005: 909-920). Interestingly, there is no strong geochemical evidence supporting this argument, and provenance study of fine ware involves limited geochemical investigation (Gogte 1997: 69- 85; Ford et al. 2005: 909-920; Schenk 2006: 123-53). Based on the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of published elemental data obtained from the analysis of South Asian fine and coarse wares from Arikamedu and Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, and local clays and modern ceramics from Anuradhapura, Magee (2010: 1043-1054) argues that prior to the 2nd century BCE fine ware production was centralised within southern India and Sri Lanka, and the South Asian fine wares, which are geochemically homogeneous, are different from coarse wares and modern ceramics from Sri Lanka. Magee (2010: 1053-54) envisages that river sediments were used in manufacturing of the potteries. However, the geochemical evidence does not help in determining the location of the production centres of the potteries primarily because the geochemical/geological source of clay has not yet been studied. This, in addition to the scarcity of published geochemical data of potteries from eastern coastal region of India (Gogte 1997: 69-85; Ford et al. 2005: 909-920), led the provenance studies to be solely based on circumstantial archaeological evidence (p.13)

However, by analyzing geochemistry of clay, they conclude ,

The uniform geochemical character of the potteries collected from Arikamedu, Chandraketugarh and Tamluk implies that the potteries have a common origin, i.e. they are manufactured using a common raw material derived from the weathering of felsic to intermediate rocks that are abundant in Tamil Nadu, but absent in the Ganga Plains. The geochemistry of the potteries does not correlate with the geochemistry of the Gangetic alluvium. Hence, it is likely that the potteries were manufactured at or close to Arikamedu, and exported to Tamluk and Chandraketugarh in West Bengal. Our study indicates that major element oxide and trace element geochemistry in archaeological potteries are useful for provenance studies of potteries collected from coastal India. (p.17)

Moreover, largest assemblage of IRW in a particular site is in western coast of India - that is, Pattanam from Kerala. Pattanam has 12,000+ IRW - more than any site in Indian ocean (Cherian 2015:749). Keezhadi excavations in two season from 2014-2016 has revealed 200+ sherd of IRW (Ramakrishna et. al. 2018:60). It is least likely that provenance of IRW could be outside the southern sub-continent and it also supported by it's distribution and recent geochemical data (S.K. Das et. al. 2017).

Shoebridge (2017), by analysing stylistic variances across the ceramics and manufacturing faults occurred during production of vessel concludes that IRW (and Arikamedu Type 10) production centers most likely around Arikamedu.

The investigation into the two ceramics in this research aims to fill a void which scientific research, to date, has failed to close. Krishnan and Coningham (1997) used thin section analysis to investigate the evolution of the Type, and this research was followed by Ford et al. in 2005 who attempted a geochemical analysis on Rouletted Ware, Arikamedu Type 10 and also Grey Ware. Other studies have been carried out such as that in Satanikota by Ghosh (1986), and also by Gogte (1997), but all have failed to provenance the ceramics in the study. Therefore, an alternative method of research needs to be constructed and developed in order to present more data which, on analysis, can reveal information about the biographies of these ceramic types. The method devised needed to consider the failure of the scientific (Shoebridge 2017:53 )

Debates have included proposals by Ford et al. who postulated that the vessels were produced in South East India, and the need for “extensive survey” was paramount to find the paraphernalia associated with pottery production (2005: 218). The controversial theories proposed by Gogte (1997) are often mentioned but also dismissed. This study argues that production is likely to take place close to its concentrated places of recovery, not in a region where a limited selection of the sherds was found as proposed by Gogte (1997) (Shoebridge 2017:431)

Diffusion of Indian Rouletted ware:

The Indian rouletted ware is found in many hundreds outside the subcontinent. We saw that IRW was more extensively used by South Indians - even if it was not originated there. In this context following should be understood.

IRW is found in Beikthano in Myanmar; Kobak Kendal (Buni Complex) and Cibutak in Java; Sembiran and Pacung in Bali; Tra Kieu, Go Cam in Vietnam; Palembang in Sumatra; Bukit Tengku Lembu in Malaysia; Qana in Yemen and Khor Rori in Oman and Myos Hormos, Berenike and Coptos in Egypt (Tripati 2017:6).

The rouletted wares found in Myos hormos, Qana, Khori Rori, Berenike and Coptos likely carried by Tamils from Muziris since the pottery is rarely found in west coast of India - Pattanam,however, is an exception here.

Chaisuwan (2011:94) says,

X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Neutron activation (NAA) were the scientific methods applied to analyse the samples of the rouletted wares chosen from Anuradhapura, Arikamedu, Karaikadu, Sembiran and Pacung. The results proved that the composition from all samples is very close. Moreover, there are other types of potteries found at Phu Khao Thong. Some of them are similar to those found in Arikamedu.

Other wares such as Fine ware 1, Fine ware 2, Fine ware 3, Fine ware 4 and Fine ware 5 from Arikamedu which show close resembles with wares found in Khao Sam Kaeo in Thailand is demonstrated through comparative studies(see Bouvet 2011).

Therefore, by tracing Rouletted ware - majorly distributed in S.India and likely originated in the same - one can see presence of south Indians across SE Asia.

Diffusion of Arikamedu Type 10 and 18:

In Bali, two sherds of Arikamedu Type 10 pottery is found along with Type 18,141, Rouletted ware and Indo-pacific beads. The Durham University has undertaken a project about Arikamedu Type 10 (see: http://community.dur.ac.uk/arch.projects/arikamedutype10/definition.html ).

I.W Ardika (2018) notes that,

Apart from rouletted wares, two sherds of Arikamedu type 10 have also been found at Sembiran. A sherd of Arikamedu type 18 was also found at Sembiran .The Sherd of apparent Arikamedu type 18c was reported from Bukit Tengku Lembu in Northern Malaya. (p.21)

Beads of glass and stone have been found in several Indonesian sites. Glass beads were discovered in several Indonesian sites including Sembiran, Gilimanuk (Bali), Palawangan (central Java), Lean Bua(Flores) and Pasemah (South Sumatra). The Sembiran beads are similar to south Indian samples in terms of raw materials and were probably manufactured at Arikamedu. (p.22)

(Fig 5: Distribution/Diffusion of Arikamedu Type 10. source:Shoebridge 2017)

At the vicinity of Arikamedu, for instance, if the pottery makers were Tamils then who are they in the society? IAS R Balakrishnan brings two terms namely kuyavaṉ and kuyatti. There was a pottery making caste in early Dravidian society called as *kuyam (DED p.160). The men were called as *kuyavaṉ and women were called as *kuyatti. The female poet Venni Kuyattiyār - author of Puram 66 - belonged to kuyam caste

Glass Trade:

Apart from potteries, glass - in forms of beads and bangles - are best indication of Indian presence in SE Asia before common era.

There were two major glass making tradition in South and Southeast Asia - mineral soda aluminium glass and Potash glass. The mineral soda aluminium (henceforth m-Na-Al) is divided into five subcategories by Dussubieux (Dussubieux et. al. 2010)

(Fig 6: Different types of Glass in South Asia)

(Fig 7: Distribution of glass type across South India, Sri Lanka and SE Asia. Black= m-Na-Al 3; Grey=m-Na-Al 1; VE=Very Early; E=Early.)

Very early glass in Southeast Asia had m-Na-Al 3. However, in later period m-Na-Al 1 type dominates. This may indication of extensive contact between southern subcontinent and SE Asia from 300 BC on wards.

All of thehigh

-

alumina soda glass found at the Iron Age sites in Cam- bodia belonged to the m

-

Na

-

Al 1 group and were found inlarge quantities and varieties of colors at Phum Snay (n=25),Phnom Borei (n=4), and Prei Khmeng (n=40)

Provenance of m-Na-Al 1 glass is in Sri Lanka and South India. These glass were used for bead making in early historic period in Sri Lankan and Tamil regions (except Arikamedu) and later might be diffused to SE Asia via maritime trade network.No primary lU-hBa glass workshop in Southeast Asia was identified in the earliest periods, suggesting that this glass was only manufactured in Sri Lanka and possibly in South India and traded as raw material or as beads to Southeast Asia. (Dussubieux & Gratuze 2013:404)

The Godawaya shipwreck found in Sri Lanka dated to 2nd c BC contained glass ingots (Muthucumarana et. al. 2014).

glass ingots are not common finds in the archaeological record and thus their discovery at the Godawaya site is important in itself because it demonstrates the maritime trade of raw glass (Muthucumarana et. al. 2014)

According to authors and O.Bopearchchi , the vessel was made in southern subcontinent and is voyaged from TN to Lanka - or other way around.

Therefore, it confirms the glass trade between Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu. It also explain why the glass found in Lanka and Tamil region are same.

In summary, the glass from both GVA 1 and GVA 2 falls into the broad category m-Na-Al, as defined by Dussubieux (2010). Although the closest subtype would be m-Na-Al 1 (hB-lU) , the GVA glass is not a perfect fit for this category since it contains less barium and potash and more lime, than the typical m-Na-Al 1 glasses. Using trace elements elements contents, it appears that the Godvaya glass samples share many chemical features with glass found or produced in Tamil coast of south India. (Lankton and Gratuze 2013:432)

Such contact is relevant to the proposed thesis work here as the glass found onboard the Godavaya shipwreck is thought to have originated in South India. In fact, many of the artifacts found onboard the Godavaya shipwreck – ceramics, stone querns, glass ingots, and iron ingots – suggest a close association with southern India. (Dimucci 2015:28)

The shipwreck also proves existence of maritime route between Tamilakam and Lanka prior to Roman contact and existence of advanced maritime technology.

The Brahmi inscription (2nd century BC) discovered at Anuradhapura mentions that the traders of Tamil Nadu engaged joint trade with ‘navika karava’ and the captain of the ship acted as the chief of the guild. (Tripati 2017:2)

The Karava(<Ta.Karaiyar) were ancient Tamil tribes and they lived in Lanka. The Sinhala Brahmi inscription read as Dameda Karava navika. The Sanskrit word navika mean navigator of the vessel.

The karaiyars [< Pdr. *karai : coast (DED p.120) ] were most likely seafarers and they did captained the vessels!

Arikamedu glass:

Arikamedu, however, gives different picture. The lU-hBa glass – or m-Na-Al 1 – is very sparse in Arikamedu unlike contemporary S.Indian and Sri Lankan sites. Therefore, it implies that particular site differ from rest of contemporary sites in the same region. The potential reason for this will be discussed below.

The glass like Arika ,Potash and m-Na-Ca-Al are common at Arikamedu. Though Arikamedu was a major bead - both glass and stone beads - making center, these glasses, as a raw material, are less likely manufactured at the site.

The glass like Arika ,Potash and m-Na-Ca-Al are common at Arikamedu. Though Arikamedu was a major bead - both glass and stone beads - making center, these glasses, as a raw material, are less likely manufactured at the site.

(Fig 8: Types of Glass in Sri Lanka and South India)

The abundance of samples with Arika compositions at the site of Arikamedu and the rarity of this type of glass elsewhere led to the hypothesis that this glass was certainly a local production even if no archaeological evidence of glass-manufacturing activities was recovered at the site. The recent discovery of m-Na-Ca-Al and Arika compositions at the site of Phu Khao Thong (Thailand) shows that the diffusion of the Arika glass could be more important than previously assumed. Besides, these results tend to show that two different trade networks exist for glass beads: one where lU-hBa glass dominates and one where the majority is m-Na-Ca-Al/Arika glasses. Also, they could question the hypothesis that the Arika glasses and possibly the m-Na-Ca-Al glass could have been manufactured at Arikamedu (Dussubieux & Gratuze 2013:409)

Arika and m-Na-Ca-Al glass found only in Arikamedu and Phu Khao Thong shows connection between these "ports". These glass must be diffused either from one to other or from common source.

We already seen pottery similarities between Arikamedu and Phu Khao Thong. Moreover, two Tamil Brahmi is found in the Khao Thong area along with an early Chola coin. Mediterranean/Roman artifacts found in Thailand (Chaisuwan 2011) probably diffused from Arikamedu. Dussubieux says that the potash and m-Na-Ca-Al glasses worked in Arikamedu most likely imported from East as part of Indo-East trade.

We already seen pottery similarities between Arikamedu and Phu Khao Thong. Moreover, two Tamil Brahmi is found in the Khao Thong area along with an early Chola coin. Mediterranean/Roman artifacts found in Thailand (Chaisuwan 2011) probably diffused from Arikamedu. Dussubieux says that the potash and m-Na-Ca-Al glasses worked in Arikamedu most likely imported from East as part of Indo-East trade.

((Fig 9: Indian Ocean in 1st century CE))

It is important to emphasize that the m-Na-Al 1 glass so abundant during the early period in South India and Sri Lanka and potash and m-Na-Ca- A/Arika glasses do not offer the same range of colours. For example, m-Na-Al 1 glass is not available in translucent dark blue, produced by cobalt, or in translucent purple, produced by the presence of manganese in the glasses.These two glasses are include in the palette of color of the Potash and m-Na-Ca-Al/Arika glasses. In south india and Sri Lanka, 23 percent of all samples that were analysed are translucent dark blue. However, dark blue glass represents 65 percent of the potash glass and 35% of the m-Na-Ca-Al/Arika glass analyzed from the same regions. This observation supports the hypothesis of the acquisition of potash and m-Na-Ca-Al/Arika glasses to extend the range of colors offered locally with m-Na-Al 1 glass, and, therefore, may identify potash and m-Na-Ca-Al glasses as "exotic" goods (Dussubieux et.al. 2012:326)

It looks plausible from the data that absence of dark blue color in locally manufactured glass forced the Tamil traders to trade for Potash and Arika/m-Na-Ca-Al glasses from SE Asia or China through Arikamedu.

Based on Glass data, Dussubieux et. al. propose three trade spheres existed during early historic period between South and Southeast Asia.

This suggests that two trade spheres may have co-existed during the early period. Because of the presence of potash glasses at very early sites, the sphere where early potash glass circulated may have been reminiscent of a more ancient trade network that was established during very early historic period. The second sphere seems to appear and develop during the early period. Because m-Na-Al 1 glass was quite likely produced in Sri Lanka and/or South India, an increase of the volume of m-Na-Al 1 glass at Southeast Asian sites suggests an increase in contacts between these two regions.

Based in the result from PKT [Phu Khao Thong] and Arikamedu, we propose that a third sphere was in place during the early period. Indeed, these two sites are characterized by an absence of m-Na-Al 1 glass and similar proportion of potash and m-Na-Ca-Al/Arika glasses. Another unusual feature of both sites is the presence of glass imports from the Mediterranean region. At Arikamedu these are in the form of gold-foil beads with a Mediterranean composition, and of fragments of containers such as ribbed bowls. Glass artifacts from the Mediterranean region are extremely rare elsewhere in South and Southeast Asia. (Dussubieux et.al. 2012:326)

Presence of Mediterranean glass - and other Mediterranean artifacts - suggests direct contact with Arikamedu, an Indo-Roman trading station in Coromandel coast. Therefore, we have all reason to suggest a direct trade between Thai coast and Coromandel coast. Periplus (v.60) also confirms it.

The glass data emphasize trade network that existed between South India and Southeast Asia from early historic period. The data also supported by pottery evidence (demonstrated above) and epigraphic evidence in form of Tamil Brahmi inscription.

By analysing pottery evidence along with glass data, epigraphic data, Arikamedu 's connection with Mediterranean, statement from Periplus (60) and verse from Pattinappalai (183-93), it is very obvious that Coromandel coast was in a nodal position in world economy. As Cobb(2018:176-78) suggested, it is very much likely that Arikamedu was the source for Roman artifacts in SE Asia.

Kannan on describing rich street of Poompuhar says,

The borders of the city with great fameare protected by the celestials. Swifthorses with lifted heads arrive on shipsfrom abroad, sacks of black pepper arrivefrom inland by wagons, gold comes fromnorthern mountains, sandalwood and akilwood come from the western mountains,and materials come from the Ganges.The yields of river Kāviri, food items fromEelam, products made in Burma, and manyrare and big things are piled up together onthe wide streets, bending the land under. (Pattinappalai: 183-93)

Kannan - author of the text - notes many minutes things that happen around the Puhar and recorded it perfectly. Though the kāḻagam mentioned in original text - in Tamil - is identified with modern state of Burma, I think it is reference to Malay/Thai peninsula. He did not mentioned what product was imported from SE Asia, nonetheless.

The original text in tamil has an important phrase 'குணகடல் துகிரும் '(kunakadal tukirum) , though missed in herber's translation. The Old Tamil word kunakadal literally means 'eastern sea' - i.e. Bay of Bengal. The Old Tamil word tukir means red coral (DED p.287).

(Fig 10: Global distribution of Coral reefs)

Kannan records shipment of horses from overseas. He,however, was not aware from where it is shipped. He also records shipment of horses in his another text called as Perumpānātruppadai (319-20).

______________

Apart from major ports, however, Tamils travelled inland.

Palanichamy et al. 2014 - a peer reviewed genetic paper published in PLoS One - concludes that two samples taken from Mesopotamia region belonging to late Roman period had closely matched with individuals from Dindigul region - a district part of Kongu region of Tamil Nadu. The apparent absence of the particular mtDNA in surrounding region and their presence in modern Dindigul district is the evident.

(Fig 11: Possible route of Tamil Merchants. source: Palanichamy et al 2014)

Therefore, cāttuḳḳal played a great role in connecting West with East and vice versa . During early historic period specialisation in gems, iron and steel, glass bead, pearl fisheries, cotton textiles and agricultural expansion helped the trade sustained for centuries - excavations in Pattanam, Arikamedu and Alagankulam revealed their heyday lasted for more than half a millennium.

As Peter Magee(2010:1052) suggests,

We suggest that the production of this new elite ware [IRW] was linked to the emerging power of a new class of maritime merchants whose wealth and prestige was increasing but was still limited to the centres they inhabited and traded from. The lucrative nature of this trade is no more clearly indicated than by the rapid growth of Arikamedu in Phase C in the first century BC. At this time, a large reservoir was constructed and along the reservoir there operated a series of workshops which produced metal, glass [beads], semi-precious stone [beads], ivory and shell [products] (Begley 1983: 472). This newly developed wealth can be contrasted to older existing forms of political-economy that were probably based on agrarian production

due to extensive contact with wider world, there was immediate reaction in the society. The Merchant guilds rose and they did called them as cāttaṉ . Specialisation in craft did arise and they also did work at other part of the world . As seen from glass data of Arikamedu, to satisfy/sustain the trade unavailable products were traded from one world and exported to another world.

Kings - or Ta. venter- showed immense interest in the trade. As Magee states, large reservoirs and ponds were built in Tamilakam around 2nd-1st c. BCE.

காடு கொன்று நாடாக்கிக்குளம் தொட்டு வளம்பெருக்கி ( பட்டினப்பாலை, 283-284 )

He [ Karikala Cholan] destroyed forests and made themIt seems the Cholan expanded Uraiyur by clearing forests , creating ponds and building palaces/mansions (Pat : 286-87). The Karikalan belongs to time period of Claudius Ptolemy (150 CE) and during this period trade was in full swing.

habitable, dug ponds, increased prosperity [of Uraiyur] (Pattinappalai 283-84)

[he] expanded his capital city of Uranthai, builtpalaces in towns where people were settled,erected big and small gates in forts and placed quivers on the bastions (Pat. 285-88)

De Romanis says, Pliny the Elder estimated Rome’s annual deficit caused by imbalanced trade with India at 50m sesterces (500,000 gold coins of a little less than eight grammes), with “Muziris representing the lion’s share of it”

Due to Indo-Roman and Indo-East trade immense wealth flowed into Tamilakam especially in capital cities and port cities. It is much reflected in Pattupattu.

A Madurai Kanchi verse describes markets in Madurai as such,

Like the ocean, with waves that batter the shores, that does not get reduced despite the clouds taking water, nor swell when the rivers bring water, the things in the market in Koodal do not get decreased by selling or get increased by new things that are brought in. (MaturaiKanci : 425-30)

In Puhar,

Like the monsoon season when clouds absorb ocean waters and come down as rains on mountains, limitless goods for export come from inland and imported goods arrive in ships. (Pattinappalai : 126-33)

Therefore, early historic period is period transition from an agrarian based economy to Industrial economy and I emphasize that during this period there was - without any doubt - organised merchant guilds were operating in Tamilagam. They did trade, from glass to pepper, with area from Coptos to Bali.

Apart from cattan and macattan, there rose kiḻavaṉ / kiḻatti - land owner/ Chief of an agricultural tract , kiḻār & uḻavaṉ - agriculturists, ūraṉ - Chief of an agricultural tract / head of village, kāviti - title awarded for best agriculturist ,kaḷamar - Inhabitants of an agricultural tract , makiḻnaṉ - head of agriculturist tracts , patan - goldsmith, vaṇikar - general trader, kuyavan - pottery maker, kaṇṇavar - ministers, tāṉai - army etc..

K Rajan comments,

Thus, the Early Historic is considered as the stage wherein the hunting-gathering/cattle raising society with kin-based societal set-up slowly moved to a state society with private community land holding pattern (Rajan 2014: 31).

For instance, in Marutam lands,

kiḻavaṉ , kiḻatti , ūraṉ and makiḻnaṉ are land owning people and superior. On the other hand kaḷamar and uḻavaṉ are workers/subordinates. On the lowest, there was aṭimai (Puram 399), paṟaiyan, tuṭiyaṉ, pāṇaṉ, and pulaiyan and they did work in agriculture tracts, palace , as bards, servants etc..

Among traders, there was vaṇikar (<Pkt. vanija) - general trader , cattan (<Pkt./Pali sarvaha)- member of the guild and macattuvan - head of the guild. Among the rulers, the venters were superior followed by velirs, mannan, kurunila mannan etc..(Rajan 2014:33-6)

_____________

Tolls and Customs in Puhar and Tondai Nadu :

In modern day world, tolls are collected in roads that leads to important centers/cities/ports etc.. In ancient world also tolls were collected by state officials in high roads.

The reference to tolls appear in Cankam texts like Pattinappalai , and Perumpanaruppadai and post Cankam text of Kural (~450 CE).

Ancient Tamils used word ulku (<Pkt. sulka)(TL:) to denote toll. The Dravidian word *vari was used to denote tax, though both words more or less mean same.

The tolls were collected and they acted as revenues to kingdom. Since Tamilakam was a place where international commerce took place, immense wealth accumulated and therefore kings collected tolls from merchants.

Analysis:

Pattinappalai verse (116-25) states,

மாஅ காவிரி மணம் கூட்டும் தூஉ எக்கர்த் துயில் மடிந்து வால் இணர் மடல் தாழை வேலாழி வியன் தெருவில் நல் இறைவன் பொருள் காக்கும் தொல் இசைத் தொழில் மாக்கள் காய் சினத்த கதிர்ச் செல்வன் தேதர் பூண்ட மாஅ போல வைகல் தொறும் அசைவு இன்றி உல்கு செயக் குறைபடாது (116-125)

English translation:

Tax collectors sleep on the pure,flower-fragrant sandy banks of the wide Kāviri and protect their fine king’s goods on the big streets near the seashore filled with thālai trees with fragrant, white clusters of flowers.They work every day without idling or taking breaks, like the horses tied to the chariot of the scorching sun with rays, and collect taxes.

The word உல்கு (ulku) (line 125) generally mean toll and/or tax. The last two lines states,

Literal English translation is,வைகல் தொறும் அசைவு இன்றி உல்கு செயக் குறைபடாது (124-25)

vaikal tōṟum acaivu iṉṟi ulku ceyaḳḳuṟaipatātu

they[collectors] do collect tolls continuously without any rest ,fail or break throughout the day!

Therefore, Tamil Kings collected tolls/tax regularly in major ports/cities to increase their revenue. From the verse, the tolls were collected throughout the day! Immense wealth could have accumulated due to tolls to the Chola state.

Ancient Tamil economic treatise Thirukkural 756 states,

உறுபொருளும் உல்கு பொருளும்தன் ஒன்னார்த் தெறுபொருளும் வேந்தன் பொருள் (குறள் 756:)

uṟupōruḷum ulku pōruḷum oṉṉār toṟupōruḷum ventaṉ pōruḷ

Unclaimed wealth, wealth acquired by tax, and wealth (got) by conquest of foes are (all) the wealth of the king.

Though Kural composed around 450 CE, it says why ulku mentioned in Cankam texts were collected. Moreover, Kural is not separated by vast time period from Cankam period.

Cankam poem Perumpanaruppadai states:

புணர்ப்பொறை தாங்கிய வடு ஆழ் நோன் புறத்து அணர்ச்செவிக் கழுதைச் சாத்தொடு வழங்கும் உல்குடைப் பெருவழிக் கவலை காக்கும் (Perum:79-81)

They [merchants] travel on wide toll roads with their donkeysThe line 81 reads as உல்குடைப் பெருவழிக்.. (ulkutai peruvaḻi) - i.e. highways with tolls. Just like modern day, there was roads with tolls and merchants had to cross it by paying toll.

with lifted ears and backs with deep scars,

that carry loads of pepper sacks, well balanced,

The Tamil word peruvaḻi generally means highroad. The medieval highway called rajakesari peruvaḻi was built by Chola king Adithan and it runs through Coimbatore region.

Epigraphically the word in it's Prakrit form is attested in Lanka.

Taxes have collected in some ports. In an inscription belonging to either the 1st or the 2nd century C.E., found in the Godawāya mentions, a sea port called Godapavatha, situated near the river Walawē. As stated in this particular inscription, “Suka,” a tax, collected in this port was donated for the maintenance of the Godapavatha Vihāraya (Paranavitana 1983 vol. ii: 101). As mentioned in this inscription the authority of collecting taxes must have vested to the monks in Godapavatha Vihāraya by the king (Gunawardana 2016:114)

The suka/sulka was collected in ancient Lankan port of Godapavatha by the monks. The Pattinappalai also projects similar scenario. However, in Puhar and Kanchipuram , tolls were collected by the officials of the Chola kingdom rather than monks/priests.

Therefore, we can hypothesis that Venters collected tolls from the merchants, though we are not in position to say if coins were used to pay the tolls. It is impossible to think that coins were not used to pay tolls. If we barter was used ,then it raises questions like what was bartered to pass the tolls and how it benefited the state - or the chiefdom?

(Fig 12: Hypothesised highways in Tamilakam)

In my last post I discussed about Chera coins in Karur and Pattanam and shared opinion of some scholars about their role. Some scholars says the coins were used in ancient Tamil ports and capital cities - at least in Cheran realm.The palghat pass played a great role in connecting Muziris and Karur. Many Roman, Greek, Chinese, Satavahana and local coins were found in and around these regions. Since palghat pass is a major trade route there must be tolls collecting stations and those coins could have used for payment of tolls. If local coins were not used for transaction then it raises the question about their purpose of existence in thousands of numbers. All three Venters, along with some chieftains/chiefdoms, issued coins. (see R. Nagaswamy's Roman Karur for local coins in Karur)

Customs officials :

In Cholan city of Puhar, the tolls were collected by officials from Cholan administration rather than priests/monks. The Pattinappalai(126-36) speaks of Cholan custom officer punching Cholan symbol on the products imported.

வான் முகந்த நீர் மலைப் பொழியவும் மலைப் பொழிந்த நீர் கடல் பரப்பவும் மாரி பெய்யும் பருவம் போல நீரினின்றும் நிலத்து ஏற்றவும் நிலத்தினின்று நீர்ப் பரப்பவும் அளந்து அறியா பல பண்டம் வரம்பு அறியாமை வந்து ஈண்டி அருங்கடி பெருங்காப்பின் வலிவுடை வல் அணங்கினோன் புலி பொறித்து புறம் போக்கி மதி நிறைந்த மலி பண்டம் (Pattinappalai 126-136)

Fierce, powerful tax collectors are

at the warehouses collecting taxes and

stamping the Cōla tiger symbols on

goods that are to be exported.

Warehouses are filled with unlimited

expensive items packed in sacks. They

lay heaped in the front yard.

Nachikinyar commentary says they were officials from Cholan administrative. From the verse, the officials were given job of punching/stamping the Cholan symbol on the product to mark the authority of the state. This suggests a systematic organisation.

The state however was actively involved in collecting road tolls on goods that carried overland and custom duties on goods brought from overseas in the major ports (Mukund 2015:35)

The following Silapathikaram verse about Puhar also confirms it.

வம்ப மாக்கள் தம் பெயர் பொறித்த கண்ணெழுத்துப் படுத்த எண்ணுப் பல் பொதிக் கடைமுக வாயிலும், கருந் தாழ்க் காவலும், (Silapathikaram: I v:110-12 )

Foreign traders who came to Puhar had their name , weight, measure stamped on their goods and they did keep their goods on the warehouse

____________________

As Mukund(2015:34-5) says, one of the major role of state is to protect the traders and trade routes from highway robbers. Whenever there is danger to trade route the state has to respond.

The obscured verse from Puram 126 (14-6) says,

சின மிகு தானை வானவன் குடகடல்,பொலந்தரு நாவாய் ஓட்டிய அவ்வழிப், பிறகலம் செல்கலாது அனையேம் அத்தை..

when Cheran sails his vessels to bring gold, angry Cheran army dont allow other boats to sail in the sea

ciṉa miku tāṉai vāṉavaṉ kutakadal

pōlantaru nāvāy ōtiya aṿṿaḻi

piṟakalam celkalātu aṉaimeyam attai..

From the verse, the angry Cheran army (ciṉa miku tāṉai vāṉavaṉ : tāṉai = Army (TL:1862) ; vāṉavaṉ=Cheran title.) did not wanted other vessels to sail in the western ocean (aṿṿaḻi piṟakalam celkalātu : kalam = small vessels) when they bring gold through their vessels (pōlantaru nāvāy ōtiya: nāvāy = huge vessel)

Why Cheran army did not wanted other boats to sail in ocean when they bring gold ?

The answer to the question can be obtained through Pliny's statement in his Natural History. Pliny says the Musiri was subjected to attacks from the pirates of Nitrias.

Pliny says, "[Muziris] was not desirable place for call, pirates in the neighbourhood". Pliny says, due to pirates, Muziris was losing it's importance to Nelcynda - a Pandyan port in Kerala and Nelcynda offered good cargo unloading service than the Muziris.

(Fig 13: Muziris in the 5th century CE Tabula Peutingeriana )

Now the Puram (126) makes good sense to us when we study it along with contemporary text. Pirates in the ocean must be causing great danger to Cheran economy and their port of Muziris. Though the verse did not mention Muziris nor Yavanas, the gold mentioned in the text must be Roman import. Romans used their gold coins as bullion. Due to piracy, the Cheran subjects did not allow other vessels to sail in the western ocean. Moreover, there are numerous reference to naval strength of Chera kings in the Sangam literature. I cannot reproduce everything here. It's beyond the scope of the subject. The occurrence of the word katalpadai (கடற்படை) - i.e. Navy - in Puram (v.6 :12) suggests existence of a navy. Existence of navy is not unlikely.

The Cheran motivation to control the piracy in the trade route through his organised army suggest a good level of political organisation under them.

Praise be to the moon… (Thingalai potrudum…)

Praise be to the Sun… (Gnayiru potrudum…)

Praise be to the rain… (Mamazhai potrudum…)

Praise be to Poompuhar… (PoomPuhar potrudum…)

Reference :

K Rajan 2011 : 'Emergence of Early Historic Trade in Peninsular India' in Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade : Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange.

Mahadevan, Iravatham 2003 : EARLY TAMIL EPIGRAPHY, Volume 62.

Mahadevan, Iravatham 2003 : EARLY TAMIL EPIGRAPHY, Volume 62.

Mahadevan, Iravatham 1970 : Tamil-Brahmi Inscriptions.

Mahadevan, Iravatham 1966: Corpus of Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions

Pusparatnam, Paramu 2002: Ancient Coins of Sri Lankan Tamil Rulers.

Zvelebil, Kamil 1992: Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature .

McLaughlin, Raoul 2010 :Rome and the Distant East_ Trade Routes to the ancient lands of Arabia, India and China-Continuum (2010).

Guy, John 2011 : 'Tamil Merchants and the Hindu-Buddhist diaspora in early Southeast Asia' in Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade : Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange.

Chaisuwan, Boonyarit 2011 : 'Early contacts between India and the Andaman coast in Thailand from the second century BCE to Eleventh century CE' in Pierre-Yves Manguin, A. Mani, Geoff Wade : Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange.

Palanichamy MG, Mitra B , Debnath M, Agrawal S, Chaudhuri TK and Zhang YP 2014 : Tamil merchant in ancient Mesopotamia.

Cobb, Matthew 2018: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE-Brill (2018)

Magee , Peter 2010 : Revisiting Indian Rouletted Ware and the Impact of Indian Ocean Trade in Early Historic South Asia

Shoebridge , Joanne Ellen 2017 : Revisiting Rouletted Ware and Arikamedu Type 10: Towards a spatial and temporal reconstruction of Indian Ocean networks in the Early Historic , Durham theses, Durham University.

Laure Dussubieux and Bernard Gratuze 2013: Glass in South Asia.

K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, Nanda Kishor Swain, M. Rajesh and N. Veeraraghavan 2018: Excavations at Keeladi, Sivaganga District, Tamil Nadu (2014 ‐ 2015 and 2015 ‐ 16)

Laure Dussubieux, James W.Lankton, Berenice Bellina-Pryce and Boonyarit Chaisuwan 2012: Early Glass Trade in South and Southeast Asia: New Insights Two Coastal Sites, Phu Khao Thong in Thailand and Arikamedu in South India

Tripati , Sila 2017: Seafaring Archaeology of the East Coast of India and Southeast Asia during the Early Historical Period.

PJ Cherian 2015: Pattanam Represents the Ancient Urban Periyar River Valley Culture: 9th Season Excavation Report (2014 ‐ 15)

Supriyo Kumar Das, Santanu Ghosh, Kaushik Gangopadhyay, Subhendu Ghosh and Manoshi Hazra 2017: Provenance Study of Ancient Potteries from West Bengal and Tamil Nadu: Application of Major Element Oxides and Trace Element Geochemistry.

Shoebridge , Joanne Ellen 2017 : Revisiting Rouletted Ware and Arikamedu Type 10: Towards a spatial and temporal reconstruction of Indian Ocean networks in the Early Historic , Durham theses, Durham University.

Laure Dussubieux and Bernard Gratuze 2013: Glass in South Asia.

K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, Nanda Kishor Swain, M. Rajesh and N. Veeraraghavan 2018: Excavations at Keeladi, Sivaganga District, Tamil Nadu (2014 ‐ 2015 and 2015 ‐ 16)

Laure Dussubieux, James W.Lankton, Berenice Bellina-Pryce and Boonyarit Chaisuwan 2012: Early Glass Trade in South and Southeast Asia: New Insights Two Coastal Sites, Phu Khao Thong in Thailand and Arikamedu in South India

Tripati , Sila 2017: Seafaring Archaeology of the East Coast of India and Southeast Asia during the Early Historical Period.

PJ Cherian 2015: Pattanam Represents the Ancient Urban Periyar River Valley Culture: 9th Season Excavation Report (2014 ‐ 15)

Supriyo Kumar Das, Santanu Ghosh, Kaushik Gangopadhyay, Subhendu Ghosh and Manoshi Hazra 2017: Provenance Study of Ancient Potteries from West Bengal and Tamil Nadu: Application of Major Element Oxides and Trace Element Geochemistry.

I.W Ardika 2018: ' Early Contacts Between Bali and India' in Shyam Saran's (ed) 'Cultural and Civilisational Links Between India and SouthEast Asia: Historical and Contemporary Dimensions'.

R. Muthucumarana , A.S. Gaur, W.M. Chandraratne , M. Manders , B. Ramlingeswara Rao , Ravi Bhushan , V.D. Khedekar and A.M.A. Dayananda 2014: An early historic assemblage offshore of Godawaya, Sri Lanka: Evidence for early regional seafaring in South Asia

Gunawardana, Dr. Nadeesha 2016: The Role of the Traders in Monetary Transactions in Ancient Sri Lanka

(6th B.C.E. to 5th C.E).

Ford, L. A. and Pollard, A. M. and Coningham, R. A. E. and Stern, B. (2005) 'A geochemical investigation of the origin of Rouletted and other related South Asian ne wares.', Antiquity., 79 (306). pp. 909-920.

Mukund, Kanakalatha 2015: Merchants of Tamilakam: Pioneers of International Trade

DiMucci, Arianna Michelle 2015 : AN ANCIENT IRON CARGO IN THE INDIAN OCEAN: THE GODAVAYA SHIPWRECK.

Appendix of Lankton and Gratuze in O.Benearapchi, Dissanayaka and Perrara 2013: 'Recent archaeological evidence on the maritime trade in the Indian Ocean: Shipwreck at Godavaya' in 'Ports of Ancient Indian Ocean'

0 Comments